Inside a Tile Engine¶

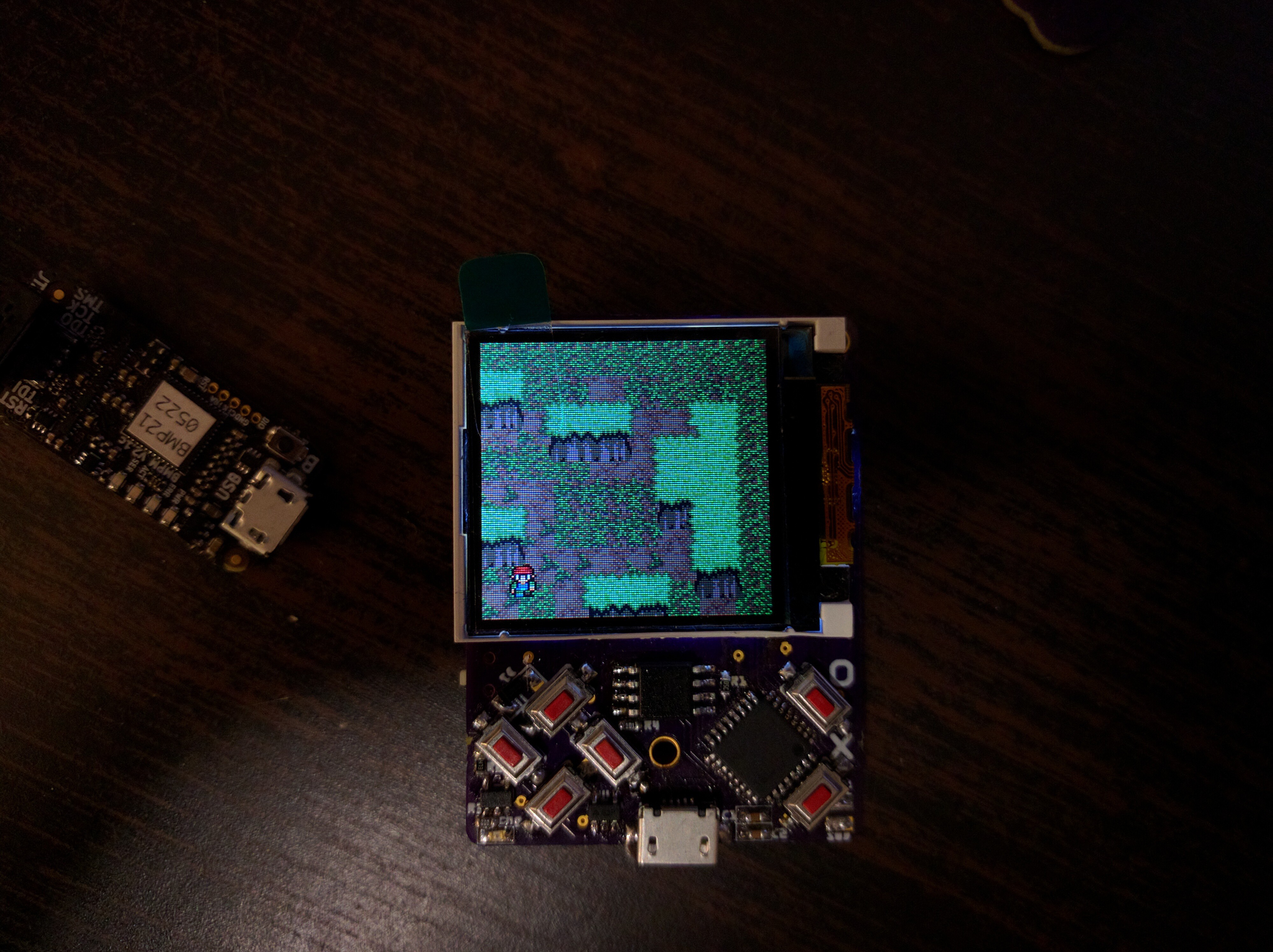

Published on 2017-10-28 in µGame.

So how does all that work? It’s simple, really, apart from all the book-keeping code for loading graphics and palettes from BMP files, accessing individual pixels in 4bpp data, and so on.

The heart of the whole thing is this method:

def render(self, x0, y0, x1, y1, buffer):

index = 0

for y in range(y0, y1 + 1):

for x in range(x0, x1 + 1):

for layer in self.layers:

c = layer.pixel(x, y)

if c != 0x1ff8:

buffer[index] = c

break

index += 1

It takes the coordinates of two corners of a rectangle and a buffer, and fills the buffer with pixel data to be sent to the display. It does that by iterating over all the pixels, and for each checking all the layers and sprites for non-transparent pixels. As soon as it finds one, it sets its color in the buffer, and goes to the next pixel. Simple.

Of course all the complexity is actually hidden in that pixel method of the layer/sprite, which needs to figure out how those coordinates map to the coordinates of the given layer, find the right square on it, get the graphic for that square, find which pixel in that graphic we want, convert it from 4-bit to 16-bit color using the correct palette, and return the color. That’s where probably 80% of the time, or more, is being spent. Fortunately, that’s all rather simple additions, bit shifts and table look-ups, so I hope that I can make it really, really fast in C.

On a side note, this is not the optimal way for doing it speed-wise. Using a blit function that would transfer whole blocks of memory would be much more efficient in terms of speed. But not in terms of memory, and I care for memory more in here than for the raw speed, which is limited by the speed of the SPI interface anyways.

deshipu.art

deshipu.art